Summer Undergraduate

Research at Cal Poly

Effects of Defects on Mechanical Strength in FDM Materials, Sponsored by Lockheed Martin

During my summer research project at Cal Poly, I collaborated with Lockheed Martin to investigate the effects of common defects in 3D printed materials on their mechanical properties. The goal of this research was to determine whether certain defects could be ignored, allowing Lockheed Martin to save costs in manufacturing. I worked under the supervision of Professors Mohsen Kivy and Xuan Wang, and was responsible for designing and printing test coupons with specific defects of interest to Lockheed Martin.

I also worked with a Materials Engineering student to conduct tensile tests on the coupons and collect data. I wrote a script to automatically process the data and analyze the resulting stress-strain curves. Our findings showed that all defects reduced the strength of the parts, but the magnitude of this reduction varied greatly between different defects. Some defects had a much greater impact on the strength of the parts than others, while others had little impact. Defects that did not significantly impact the overall mechanical strength of the material could still be used in the final product. This meant that the prints could be used, as long as the defects did not compromise the integrity of the part. By simulating these types of defects in our tests, we could better understand their impact on the finished product and make informed decisions about whether to use the prints in the final design. These results generated significant interest from our collaborators at Lockheed Martin.

Main Challenges

One of the main challenges with this project was figuring out how to simulate defects in 3D printed parts. Initially, we considered modifying the 3D printer itself to increase the likelihood of defects, but this approach had several drawbacks. For one, it wouldn't allow us to test specific defects. Additionally, there was a risk of damaging the printer beyond repair.

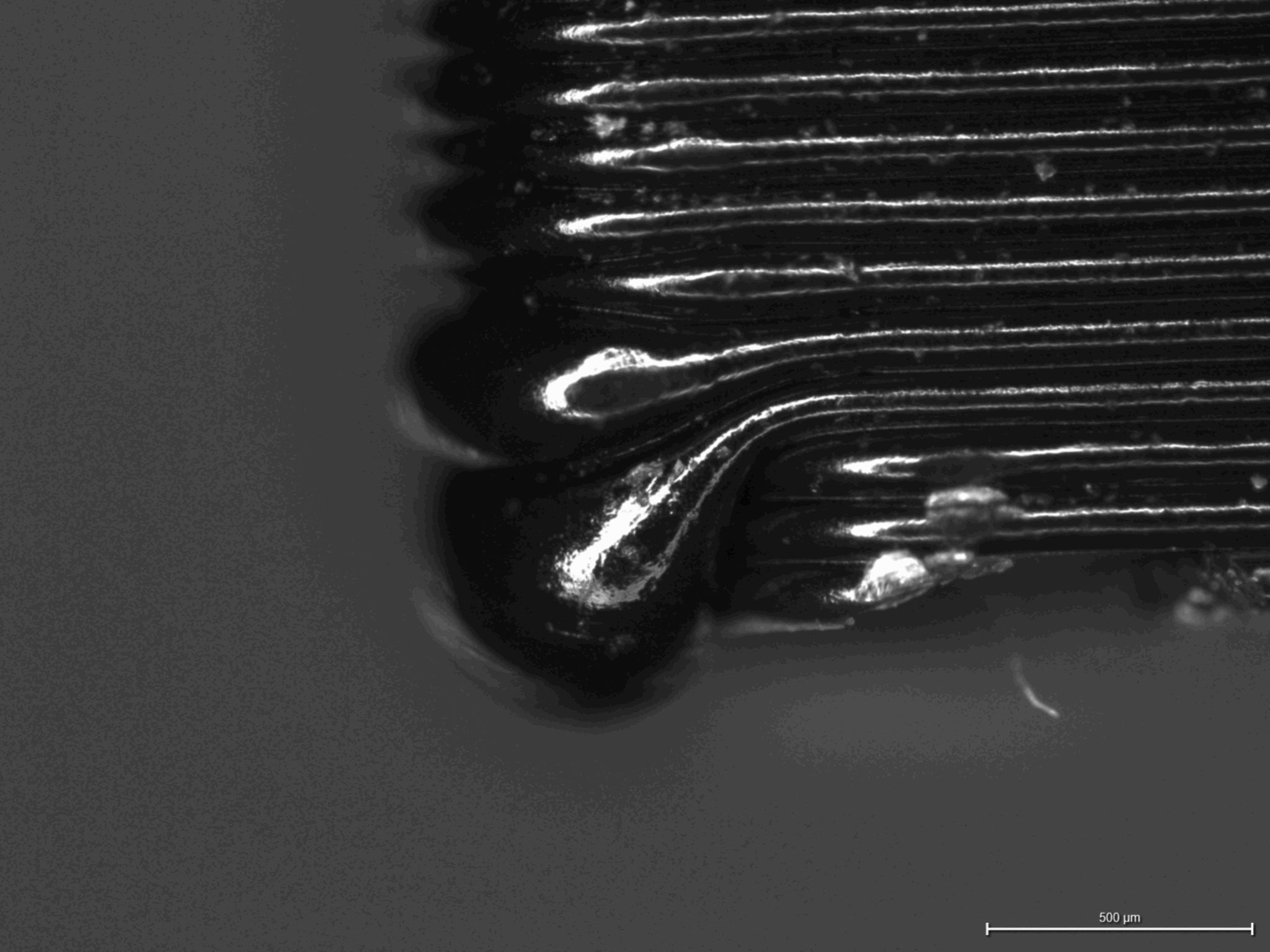

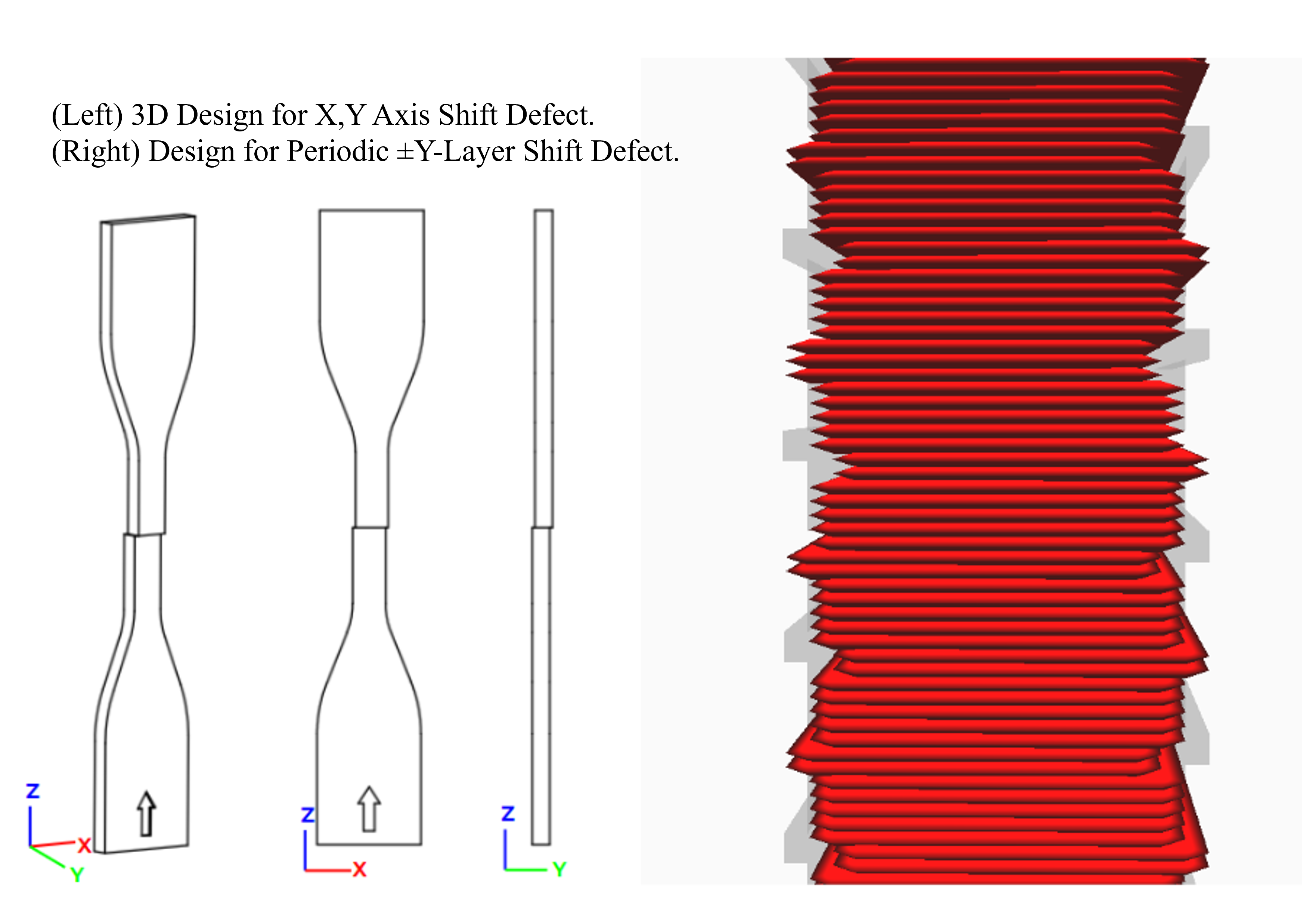

To address these issues, I suggested using computer-aided design (CAD) to modify the prints themselves. By controlling the layer height of the print, we could create designs that simulated different defects. These results are shown in Figure 9. While this method wouldn't perfectly replicate naturally occurring errors, it was deemed sufficient for our testing purposes, and was approved by Lockheed Martin.

Another challenge we faced was the tedious process of analyzing data collected from our tensile test machine. Since the results for each sample were saved in separate Excel sheets, we had to open each sheet individually and use Excel functions to analyze the data. This was time-consuming and made it difficult to compare the results of different samples. To address this, I developed a MatLab script that could automatically process all of the data from the tensile test machine. The script went through all of the Excel sheets, separated them by sample type and date, and converted the testing data into standard units. It then plotted all of the data and calculated key measurements, such as ultimate tensile strength, yield strength, and elongation until break. The program also found the averages of these measurements for each defect set and calculated the standard deviation, letting us quickly analyze the results of our tests. This allowed us to go from spending up to 4 hours on data analysis per testing session to just 5 minutes.

Full Poster Report